White Feathers of Midlothian

THE GROWTH OF THE PALS BATTALIONS was fuelled in part by a spirit of local rivalry deliberately fostered by the War Office. Towns and cities competed with each other in an effort to fulfil their patriotic duty. As the military crisis deepened in France, the pressure to ‘volunteer’ became unbearable. The League of the White Feather encouraged its members to publicly shame any young man who was seen out-of-doors in civilian attire.

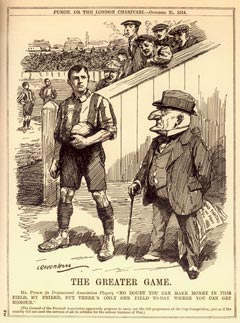

Against this background of intimidation and intolerance, professional football, of all things, became the target of an orchestrated campaign of abuse, led by the wealthy London brewery heir, Frederick Charrington. Footballers, said the critics, were shirkers and cowards, content to hide at home while better men risked their lives at the front. Football was a ‘moral scourge’ and the Government should take measures to ‘stop’ it forthwith. This position, as indefensible as most of the makeshift British trenches in France, reflected a narrow pre-war opinion that professional sport was somehow corrupting the spirit of the nation’s youth. A famous cartoon in the satirical magazine, Punch, evoked thoughts of a ‘Greater Game’ – played not for trophies but for honour on the field of battle.

The principal target of this vitriol was the Edinburgh team, Heart of Midlothian – then leaders of the Scottish League and considered by contemporary observers to be the finest football combination in Great Britain. Scotland, at the time, was renowned as the home of the ‘scientific’ game, characterised by quick passing and swift, intelligent movement. Clearly such players would make excellent soldiers. A letter to the press, renaming the club ‘White Feathers of Midlothian’, presaged a stream of angry and insulting missives. Many included detailed directions to the nearest recruiting office.

The anti-football campaign reached the House of Commons on the afternoon of 26 November 1914. Sir John Lonsdale, Unionist M.P. for Mid Armagh, asked the Prime Minister, the Right Honourable Herbert Asquith, if he would ‘introduce legislation taking powers to suppress all professional football during the continuance of the war.’ His timing couldn’t have been worse. The previous afternoon eleven Heart of Midlothian players had enlisted in a new battalion which was being raised in Edinburgh by the politician and businessman, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir George McCrae. Since then, a further two players had joined them. News of the ‘Edinburgh Sensation’ had already reached the London papers. Asquith was able to refer to it in his response, defusing the situation with no little ease.

The ‘stoppers’ were repulsed. Hearts, noted The Scotsman, had saved the good name of British football.

The Hearts have led the way!

The Hearts have saved the day!

These brave young Hearts,

Edina’s Hearts.

We’ll follow

Come what may!

(Private George Blaney, 16th Royal Scots, December 1914)