The Voluntary Principle

CONTINENTAL COUNTRIES favoured compulsory military service. On the outbreak of war Germany mobilised almost four and a half million trained soldiers – of whom one and a half million were deployed on the western front within a fortnight. By comparison Great Britain’s Expeditionary Force – allegedly described by the Kaiser as a ‘contemptible little army’ – embarked for France with fewer than 90,000 officers and men.

On 5 August Prime Minister Asquith convened a war council at 10 Downing Street. Present (among others) were First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill; Lieutenant General Douglas Haig, commander designate of 1 Army Corps; and Lord Kitchener. Kitchener and Haig astonished their colleagues with their blunt assessment of the situation. The war would last (in Kitchener’s opinion) at least three years and would require the creation of an army of one million men. Great Britain and the Empire were engaged in a struggle for their very existence.

Notwithstanding the gravity of the crisis, it was agreed that the voluntary principle must continue to prevail. The British people would have no truck with conscription. On 7 August Kitchener made his famous appeal for a hundred thousand volunteers between the ages of 19 and 30. ‘Kitchener’s Army’, or ‘K1’, was raised within a fortnight and reinforced at the end of August by a second hundred thousand (‘K2’) with the upper age limit extended to 35.

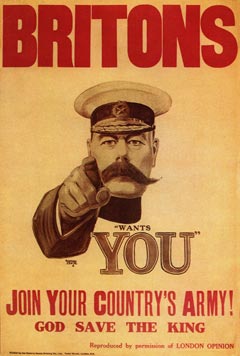

On the 6th of September His Lordship appeared on the cover of the influential magazine London Opinion enjoining young men to enlist with the words ‘Your Country Needs You!’ The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee quickly adapted Alfred Leete’s artwork into a striking poster, which was pasted on to walls and billboards nationwide. The third of the New Armies (‘K3’) came next as the mood of patriotic urgency was sustained, followed by a fourth (‘K4’) during the closing months of the year. More than a million men had volunteered by January 1915.

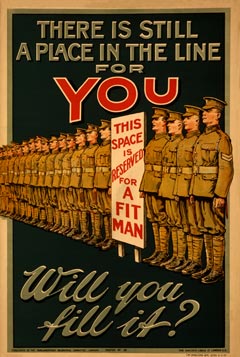

In raising K4 the War Office adopted a new approach – the commissioning of dedicated committees all over the country, led by patriotic local businessmen and councillors. Prospective recruits were offered certain inducements – most notably that they would be allowed to serve ‘for the duration’ with their friends. In response, workmates, team-mates, schoolmates, brothers, cousins, fathers and sons marched proudly to the Colours in the name of their town, their city, their profession or their trade. The ‘Pals’ battalions (as they became known in England) were born in an atmosphere of naive optimism; they would die within eighteen months in a tragedy that should have been foreseen.