The Sporting Battalion

ON SATURDAY 15th AUGUST 1914 Heart of Midlothian defeated reigning champions Celtic 2-0 at Tynecastle in the inaugural fixture of the new football season. The war was ten days old. Hearts had already lost two players to the military. Territorial Neil Moreland had been mobilised with his infantry battalion; George Sinclair, a former Regular with the Royal Field Artillery, had been recalled to the Colours.

The following Monday former Hearts director Harry Rawson, chairman of the Edinburgh Territorial Force Association, asked manager John McCartney if the club would use its influence to encourage recruiting. McCartney agreed to allow the authorities access to Tynecastle on match days in order to canvass for volunteers. On 20 August he announced that the entire playing staff would take part in weekly drill sessions to prepare them for the possibility of military service. These would be conducted by the club’s reserve half-back, Annan Ness, who was a former soldier. McCartney also extended an invitation to the players of local rivals Hibernian to join in. Several accepted.

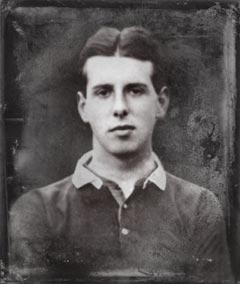

Hearts’ captain, Robert Mercer was unable to participate. He had sustained serious damage to his knee in the victory over Celtic. He returned to the side in October, only to break down once again. Mercer, however, remained Hearts captain – the most prominent player at the most prominent club in Scotland. The anti-football movement found its target, and he began to receive letters advising him to enlist. Some were friendly, some were cold. Some were downright sinister. Tom Gracie suffered, too. On the morning of the match against Queen’s Park at Hampden on 24 October, the centre-forward opened an envelope to find a copy of the Punch cartoon that was inspired by Mr Charrington’s anti-football campaign. There was no signature.

On Saturday 14 November Hearts, who remained comfortable leaders of the League, entertained Falkirk. In that morning’s Glasgow Herald the chairman of Airdrieonians cast doubt on the War Office’s support for continuation of the game. Other papers carried speculation about the introduction of compulsory military service. And of course there was black news from the front, where the position of the British Expeditionary Force was growing more perilous by the day. At half-time the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders made an urgent appeal for volunteers: the initial response was disappointing, but at full-time several men stepped forward. Among them was Tynecastle winger James Speedie.

‘Three Hearts men with the Colours now!’ announced the Evening Dispatch. Speedie headed north to Fort George, near Inverness, where his regiment was training. Then on 16 November the Evening News published a letter from ‘Soldier’s Daughter’, who suggested ‘that while Hearts continue to play football, enabled thus to pursue their peaceful play by the sacrifice of the lives of thousands of their countrymen, they might adopt, temporarily, a nom de plume, say “The White Feathers of Midlothian.”…’

***

On Wednesday 25 November 1914 Sir George McCrae held a press conference in the Tynecastle boardroom and announced the enlistment of eleven Hearts players in his new battalion: Alfie Briggs, Duncan Currie, Tom Gracie, Jamie Low, Harry Wattie and Willie Wilson from the first team; and Ernie Ellis, Norman Findlay, Jimmy Frew, Annan Ness and Bob Preston from the second. A further five players (including Mercer) had been turned down for medical reasons by the examining doctor. The news caused a national sensation and was perfectly timed to defuse the anti-football campaign. When Mr Charrington’s representative stood up in the House of Commons to demand immediate suspension of the professional game, Prime Minister Asquith was able to cite Scotland’s example in his devastating dismissal. Hearts (most notably, the Hearts players) had saved their sport. Professional footballers had been volunteering ever since the outbreak of war; but none so concertedly, so selflessly and so publicly. The slings and arrows directed at football were always undeserved; but the Tynecastle enlistment was the blow required to silence the critics, ensure continuation and preserve the game’s good name.

On 26 November two more players enlisted. Pat Crossan and Jimmy Boyd brought Hearts’ total of ‘soldier footballers’ to sixteen, a figure unequalled in the United Kingdom and a figure that would almost double over the next two seasons.

It was a tumultuous opening, the start of what seemed like a glorious adventure. The end (of course) was darker and descended into tragedy. Seven Hearts players gave their lives in the war and others (like Alfie Briggs) were physically and mentally traumatised after they returned from active service. The club’s Roll of Honour is a sobering document:

1. McCrae’s Battalion

| James Boyd | Killed in action, 3 August 1916. | |

| Alfred Briggs | Wounded in action, 1 July 1916; discharged invalid. | |

| Patrick Crossan | Wounded in action twice; gassed; discharged invalid. | |

| Duncan Currie | Killed in action, 1 July 1916. | |

| Ernest Ellis | Killed in action, 1 July 1916. | |

| Norman Findlay | Discharged to trade, September 1916. | |

| James Frew | Transferred to 1st Lowland (City of Edinburgh) RGA. | |

| Thomas Gracie | Died on service, 23 October 1915 | |

| James Hazeldean | Wounded in action, 1 July 1916; discharged invalid. | |

| James Low | Commissioned 6th Seaforth Highlanders; wounded in action twice. | |

| Edward McGuire | Wounded in action, 1 July 1916; discharged invalid. | |

| Annan Ness | Twice wounded; commissioned 16th RS; Lt 9th RS. | |

| Robert Preston | Transferred to HLI; wounded in action. | |

| Henry Wattie | Killed in action, 1 July 1916. | |

| William Wilson | Transferred 13th RS; returned to 16th RS; wounded in action. |

2. Other units

| John Allan | 9th Royal Scots. Killed in action, 22 April 1917. | |

| Colin Blackhall | 1st Lowland (City of Edinburgh) RGA. | |

| James Gilbert | 1st Lowland (City of Edinburgh) RGA. | |

| Harry Graham | Gloucester Regiment; transferred to RAMC. | |

| Charles Hallwood | Royal Engineers | |

| James Macdonald | 13th Royal Scots. | |

| John Mackenzie | 1st Lowland (City of Edinburgh) Royal Garrison Artillery. | |

| Robert Malcolm | Royal Scots; transferred to Machine Gun Corps. | |

| John Martin | 5th Royal Scots; twice wounded; discharged invalid. | |

| Robert Mercer | 1st Lowland (City of Edinburgh) RGA; gassed; discharged invalid. | |

| George Miller | 9th Royal Scots; wounded. | |

| Neil Moreland | 8th HLI; transferred to 7th Royal Scots; wounded three times. | |

| George Sinclair | Royal Field Artillery; injured on service; discharged 1915. | |

| James Speedie | 7th Cameron Highlanders; killed in action, 25 September 1915. | |

| Philip Whyte | City of Edinburgh Fortress Company, RE; Gloucester Regiment. | |

| John Wilson | 9th Royal Scots; wounded in action twice. |

3. Roll of Dead

| John Allan | Killed in action on 22 April 1917. | |

| James Boyd | Killed in action on 3 August 1916. | |

| Patrick Crossan | Died on 24 April 1933. | |

| Duncan Currie | Killed in action on 1 July 1916. | |

| James Duckworth | Died on 25 August 1920. | |

| Ernest Ellis | Killed in action on 1 July 1916. | |

| Thomas Gracie | Died on 23 October 1915. | |

| Alexander Lyon | Died on 14 February 1915. | |

| Robert Mercer | Died on 23 April 1926. | |

| James Speedie | Killed in action on 25 September 1915. | |

| Henry Wattie | Killed in action on 1 July 1916. |

Tom Gracie, Scotland’s leading goalscorer, died of leukaemia at Stobhill Hospital, having hidden the illness from almost everyone until the last moment. Bob Mercer’s cruciate injury should have kept him out of the Army, but he was conscripted in 1916 and suffered severe damage to his lungs during a German gas attack in 1918. He re-signed for Hearts after the war but was never the same player. He retired in 1924. He was persuaded to return for a farewell appearance in a friendly match against Selkirk at Ettrick Park. A few minutes into the game he suffered a fatal heart attack. Crossan’s end was similar; he succumbed to his gas injuries seven years later.

Duckworth and Lyon contracted their illnesses while accompanying McCrae’s Hearts players on route marches and manœuvres during the winter of 1914–1915. Boyd, Currie, Ellis and Wattie died on the Somme and are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, near the village of Thiepval.

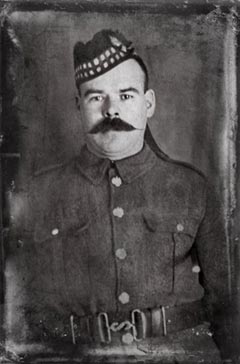

It’s likely that Currie is one of the unidentified burials at Gordon Dump Cemetery, near la Boisselle. His body was originally buried beside his officer Lionel Coles in a temporary grave, which was close by. When Gordon Dump was formally laid out, Coles was re-interred; presumably Duncan isn’t far away. The remains of Boyd and Ellis were found and buried in 1916 and 1917 respectively; subsequently, however, the locations of their graves were lost. No trace of Wattie has ever been found. Speedie’s battalion was almost destroyed at Loos. One of his pals said he’d seen him mid morning in the chaos on the southern slope of Hill 70, just in front of Cité St Laurent. But there was nothing more. The survivors of 44 Brigade withdrew, leaving their dead behind. Jimmy (right) has no known grave, so he’s commemorated on the Loos Memorial at Dud Corner Cemetery. His brother, John, who almost signed for Hearts, was killed in June 1917 as a subaltern with 15th Royal Scots. He’s buried in the Arras suburb of St Laurent-Blangy.

John Allan always seems to be overlooked. He signed for the club from Tranent Juniors in 1915 as cover for Robert Mercer. In 1916 he was sent in a draft to France to reinforce 9th Royal Scots. In the early hours of 22 April 1917 he was wounded during a bloody assault on the village of Roeux. No trace of him could be found after the engagement. His name is carved on the Arras Memorial at Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery – not far from that of 2Lt David Philip of 23rd Northumberland Fusiliers, who played at left back in Hearts’ 1906 Scottish Cup-winning side.

All the men listed above were employed by Heart of Midlothian Football Club at the time of enlistment or mobilisation and continued to be employed by the club (on reduced wages) until the end of hostilities. The list of former Hearts players and guest players who served or gave their lives in the Great War is substantially longer. Heart of Midlothian unveiled a handsome memorial clocktower in Edinburgh’s busy Haymarket junction on 9 April 1922, the fifth anniversary of the opening of the Battle of Arras. Secretary for Scotland, the Right Honourable Robert Munro, told the crowd of 65,000 that the country owed a debt of gratitude to Hearts that could never be repaid. In 2013, following a period in storage during tramway construction, the Heart of Midlothian War Memorial returned to its spiritual home in time to mark the hundredth year since the start of the Great War and the formation of McCrae’s Battalion.

***

McCrae’s was the first of the ‘Footballers’ battalions – inspiring the formation of the 17th Middlesex in England the following year. The Hearts lads were joined by players from Raith Rovers, Falkirk, Dunfermline, Hibernian, St Bernard’s and East Fife – along with representatives of around 75 other clubs of different levels. And supporters of those clubs swelled the ranks further. During the entire course of the war the 16th Royal Scots football team remained undefeated against all challengers – even after the leading players had been killed or wounded. That is a striking measure of the battalion’s football pedigree. But by 1915 the Scottish press was also describing McCrae’s as Scotland’s ‘Sporting Battalion’.

There were rugby players in McCrae’s – like Scottish international, John Dallas, who’d played against England at Richmond in 1903. And Jim Davie of Daniel Stewart’s, who was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry on the first day of the Somme. Arthur Flett (left) of Edinburgh Wanderers, Secretary of the Scottish Rugby Football Union in 1914, was killed in action at Arras. We don’t know how many rugby men volunteered, but the number of lads in the battalion who went to rugby-playing schools suggests that the oval ball was almost as familiar as the round. The finest soldier in the battalion (according to his mates) was Finlay MacRae (below right) from Inverness, who kept goal for Scotland’s international hockey team. Finlay was awarded two Military Medals before he was killed in action at Hargicourt in August 1917.

Amongst the officers and men, there were athletes of all sorts – from eccentric practitioners of ‘pedestrianism’ to explosive sprinters like Pat Crossan, who supplemented his football income by competing on the professional circuit under a variety of assumed names. Journalists who monitored such things believed he was the quickest man in Scotland over 100 yards. Harry Harley was perhaps more typical. He just enjoyed running and was a keen member of Edinburgh Northern Harriers. Harry was killed on the first day of the Somme. George Simons liked his football but he bowled for his works team. Flat-green, of course.

George was killed in 1917, near Passchendaele. Napier Armit played cricket for Grange. He was killed in August 1916 during the ill-fated assault on Intermediate Trench. His wife, Jessie, took three years to accept the official announcement of his death. Murdoch McLeod was the strongest man in Scotland – a bull-necked veteran of a thousand unlikely challenges in which he had never been bested. Murdoch’s physique was no protection against machine guns, however, and he, too, was killed on the first day of the Somme. You’ll find him in Gordon Dump Cemetery, not far from Contalmaison. His grave looks no different to any of the others but it commemorates one of the most remarkable men of his ill-fated generation.

John McNee was another bowler but his main sport was billiards. He died of wounds in October 1917. Tom Grainger Stewart was an archer. Ned Barnie loved swimming so much that he decided to take on the English Channel. In 1951 he became the oldest man to make the crossing in both directions. He was at least part whale. James White was a motor cyclist. Allan Hynd preferred bicycles. Without spectacles he was almost blind. Allan was killed on the Somme in 1916. Gymnasts, wrestlers, shot-putters, hammer-throwers, boxers, tennis players. There were few sports that weren’t represented in McCrae’s. Including shooting – which came in handy later on. The Colonel was a marksman but he preferred golf. After fitba’ and rugby, the small, white, infuriating ball was the most popular in the battalion. Arthur Grant, professional at Le Touquet, came home specifically to volunteer for the 16th Royal Scots. Sir George collared him for lessons.

At the front of Heriot’s School, there’s a large expanse of green, where Sir George was in the habit of practicing his swing. The adjoining tenements in Forrest Road had large windows. It was said that the Colonel’s faultless honesty was exceeded only by the size of the repair bills. Sir George McCrae was a sportsman – and so were his boys.