The First of July

IN THE HOUR BEFORE ZERO almost a quarter of a million shells were fired at the German position in a last desperate ‘hurricane’ bombardment. Between 7.20 and 7.28 ten mines were exploded under the opposing front-line. The scars can still be seen today at Beaumont Hamel, La Boisselle and Fricourt. Two minutes later the assaulting battalions climbed out of their assembly trenches and moved at steady pace towards the enemy. As the barrage lifted, German Maxim teams scrambled from deep dug-outs and set up their guns. The wire had not been destroyed and as the attackers bunched together at the gaps, they were cut down in their hundreds.

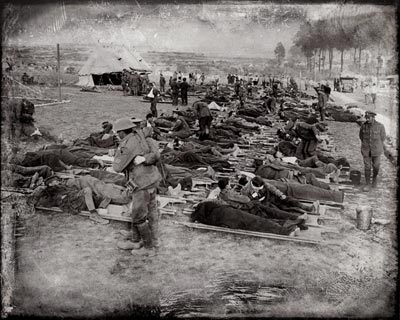

Within the first hour of the offensive it is estimated that British losses approached 30,000 officers and men. By the end of the day that figure had doubled. Almost 20,000 were dead. It was the blackest reverse in British military history. The capture of Mametz and Montauban (in the southern sector) was scant consolation. At Thiepval the magnificent 36th (Ulster) Division advanced almost a mile but were wiped out in the process; at Beaumont Hamel the 1st Newfoundlands lost 684 men – ninety per cent of their attacking strength. At Fricourt the 10th West Yorkshires lost 710 men and all but ceased to exist. It was the same story all along the line.

The Pals Battalions had taken twelve months to train; they were destroyed in a matter of minutes. Their home towns were shattered. London sustained 5,000 casualties; Manchester 3,500; Belfast 1,800. Leeds, Bradford, Birmingham, Glasgow, Newcastle and Edinburgh each lost over a thousand killed and wounded. The smallest communities were worst hit – Accrington, Barnsley, Grimsby, Cambridge and all the Tyneside pit villages that spawned the Irish and Scottish brigades of 34th Division. Newfoundland would never recover. ‘1 July marked the end of it all,’ wrote 2/Lt James Stevenson of the 16th Royal Scots. ‘I was never the same after that day. I never had such friends. And, for a while, I thought I would never smile again.’

34th DIVISION attacked in the centre, astride the main road to Bapaume. The British front line trenches lay at the foot of two shallow valleys – ‘Sausage’ and ‘Mash’ – so that the advance had to be carried steeply up the opposing slopes into the strongest defensive position in the entire sector. The fortified village of La Boisselle protected the road; the fortified village of Contalmaison awaited any troops who were able to penetrate the complex network of strongpoints and switch lines that covered the fields in between. Wire entanglements 6 feet high and 15 yards across were laid in close proximity to each other and covered by a multitude of highly mobile machine-guns.

Inky Bill placed the Tyneside Scots of 102 Brigade on his left; 101 Brigade (including McCrae’s and their sister battalion, 15th Royal Scots) took the right. Behind them, in the supporting wave, came the Tyneside Irishmen of 103 Brigade, whose advance would begin in the open, on the exposed forward slopes of Tara and Usna hills.

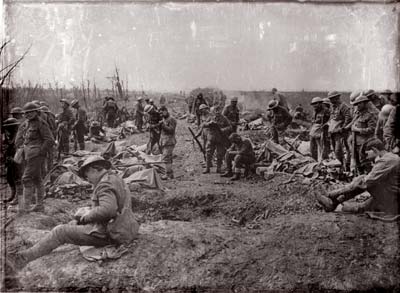

At Zero two huge mines (‘Y Sap’ and ‘Lochnagar’) were detonated either side of La Boisselle. The infantry rose up ‘as one man’ and slowly advanced. Within half an hour the Tyneside Scottish brigade had gone: they fell in no man’s land beside their mates from the supporting battalions of the Tyneside Irish. The left flank of 101 Brigade, the 10th Lincolns and 11th Suffolks, didn’t last much longer. They were cut down by flanking fire from machine-guns in the ruined cellars of La Boisselle. On the right, however, there was some progress. Elements of 101 Brigade, followed closely by survivors from 103 Brigade, fought their way through the enemy lines and captured the strongpoint known as Scots Redoubt. From here small parties continued the advance towards Contalmaison. Few survived these sorties, but we know that men from 16th Royal Scots and 27th Northumberland Fusiliers entered the village – only to withdraw soon afterwards. It was the deepest penetration of the German position on the front that morning.

The garrison of Scots Redoubt held out for three days and nights and was credited with ‘anchoring’ the modest gains to the south. The cost, however, was high. 34th Division’s casualties were close to 7,000. McCrae’s Battalion lost 12 officers and 573 men – more than three-quarters of its attacking strength. Three Hearts footballers had fallen – Harry Wattie, Duncan Currie and Ernie Ellis; a fourth, Jimmy Boyd, would join them within the month. Peter Ross, head maths teacher at Edinburgh’s Broughton Higher Grade School, wrote on 30 June: ‘I know not what awaits myself tomorrow; but I put my trust in God and go to do my duty with one of the finest companies in the British Army.’

Peter came from Thurso, in Caithness. He was shot dead near Wood Alley at around 8.30 in the morning. By noon his company no longer existed.