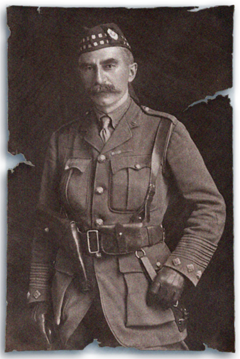

Sir George McCrae

SIR GEORGE McCRAE was not the product of a privileged childhood. He was born in Aberdeen in 1860 and raised by his stonemason uncle in the slums of Arthur Street on the southside of Edinburgh’s Old Town. He left school aged 9 to work as a bootmaker’s message boy and was apprenticed to a hatter the following year. At 16 he was placed in charge of the firm’s Dunfermline branch; by the age of 21 he had opened a rival business in Edinburgh, just down the hill from his erstwhile employer, who promptly fled the city in confusion.

A meteoric career in local politics was followed by election to Westminster in 1899 as Liberal Member for East Edinburgh. He was devoted to his family – wife Lizzie and nine children – and filled what passed for his spare time by rising through the ranks of the Volunteers from humble private to colonel of his own teetotal battalion, the 6th Royal Scots, affectionately known as ‘McCrae’s Water Rats’. In 1909 Sir George left Parliament at the request of Prime Minister Asquith to assume control of the Scottish Local Government Board – effectively becoming Scotland’s most powerful civil servant – with responsibility for implementing the Liberal Party’s ambitious programme of social reform north of the border.

In 1913 he resigned his command in order to care for his wife, who was suffering from terminal cancer. She died in December of that year and during the months leading up to the outbreak of war McCrae retired to his George Street office to bury himself in his work. In August 1914 he made no public comment on the international situation; nor, once hostilities had been declared, did he appear on any public platform enjoining young men to enlist.

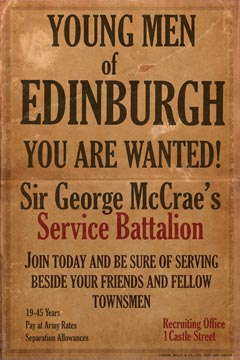

The position of Great Britain’s tiny Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders daily grew more perilous, but it was November before he broke his silence. On the 19th of the month the Evening Dispatch announced that Sir George had volunteered for active service. The following morning The Scotsman reported that the War Office had accepted his offer to raise and command a battalion in the field. George Street was besieged. Questioned by reporters among the crowd, he announced that recruiting would commence on 27 November at a grand public meeting in the Usher Hall. The campaign, he insisted, would be short; seven days, at the most, before a full complement was secured. Edinburgh’s first New Army battalion – sponsored by the Lord Provost – had taken almost as many weeks to fill, but McCrae’s trump card was the finest football team in the country.

Among the public figures responsible for raising the battalions of K4, Sir George was unusual. Far from insisting that it was the duty of young men to go, he was inviting them to come with him. At the Usher Hall, on a chill and foggy Friday evening, he made a rousing speech that would be long remembered by everyone present. ‘I would not, I could not,’ he stated simply, ‘ask you to serve unless I share the danger at your side.’

He was 54 years old.

Within a week Sir George had his men – 1,350 of them. The Hearts players were joined by fellow professionals from Raith Rovers, Falkirk, Dunfermline, Hibernian, St Bernard’s and East Fife. Falkirk could boast one of the finest sides in the country – having won the Scottish Cup in 1913 and finished runners-up to Celtic in the League twice in the previous six seasons. In total, around 75 clubs provided volunteers – most from Edinburgh, the Lothians, Linlithgowshire and Fife.

Hundreds of supporters volunteered at the Palace Hotel recruiting station in Castle Street to serve beside their idols – including a substantial contingent from Hearts’ great city rivals, Hibs. Rugby players, golfers, strongmen and athletes of all persuasions completed the ranks of what was immediately dubbed ‘McCrae’s Battalion’.

It was a title they would guard with pride until the last survivor died.