Fundraising and Construction

IN 2003, while I was completing the manuscript for McCrae’s Battalion, I took a phone call from a Hearts supporter, who was a serving sergeant with Lothians and Borders Police. Jim Paris was an amateur historian and occasional battlefield tour guide with a passion for the American Civil War and the Great War. Jim introduced himself and told me he’d heard about the forthcoming publication of my book. It so happened that he had lately suggested to Hearts that a small memorial should be placed somewhere on the Western Front to commemorate the players’ sacrifice. The club would be grateful for any advice I might be willing to impart; if I were invited to a meeting at the ground, would I come? A few days later a further phone call (this time from Hearts security manager, Tom Purdie) set in train a chain of events that continues to confound me to this day.

I arrived at the meeting somewhat nervously, very aware that the club’s priority would inevitably be its own people. On that first occasion I met Jim and Tom, together with the club historian, David Speed and the head of the Federation of Heart of Midlothian Supporters’ Clubs, Robin Beith. They were later joined by Alan Owenson, secretary of Prestonpans Hearts. The conversation opened with an airing of the club’s tentative commemorative scheme (which turned out to be very much the personal initiative of Jim and Tom). They had formed the Hearts Great War Memorial Committee with a view to installing a monument somewhere in France or Belgium. I still feel slightly self-conscious about my response, which initially addressed the Hearts memorial but quickly veered off into a discursive account of the disappointment of a group of very proud (and very angry) old men – none of whom now remained alive, but some of whom happened to have been Hearts supporters. I explained about the long struggle to build a fitting memorial to McCrae’s and pointed out that on the back of publication I was going to make a further attempt to resurrect D.M. Sutherland’s cairn. It’s immensely to the credit of the members of the Great War Memorial Committee that they immediately decided to endorse my idea – although I’ve always seen it as a decision to endorse D.M. There was one jarring moment – Tom’s insistence that the memorial be planned, constructed and unveiled within a year. Undoubtedly a man after Sandy Lindsay’s heart!

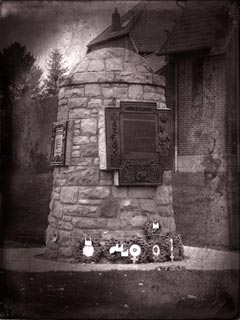

I unearthed an original sketch of the proposed cairn and Tom showed it to his friends at Watson Stonecraft in West Lothian, who in turn produced professional architectural drawings. In the meantime I designed four commemorative bronze plaques – one of which would serve as the Hearts memorial that had brought us together in the first place. The imagery was drawn from original battalion photographs and artwork – most notably D.M. Sutherland’s 1916 Christmas card with its cartoon of a soldier in a dug-out, outsmarted by a thieving rat sitting contentedly in the sock where he’d hidden his chocolate. That’s the soldier’s chocolate – not the rat’s. A proper McCrae’s memorial would have to have some humour somewhere – humour and an image of the Colonel. Orkney sculptor, Gary Gibson was commissioned to turn my montage of sketches and images into clay moulds – a principal plaque for the front, incorporating Edinburgh’s coat of arms; the cap badge of the Royal Scots; the chequerboard emblem of the deathless 34th Division; D.M.’s (equally deathless) cartoon; and a superb relief of Sir George McCrae. Then the first of the supporting plaques – for Heart of Midlothian – with the club crests (old and new) superimposed on a barbed wire tangle of thistles and poppies and the smiling figure of Jimmy Brown, the battalion’s shortest (and most cantankerous) volunteer at just under five foot tall.

Come pack up your footballs and scarves of maroon.

Leave all your sweethearts in Auld Reekie toon.

Fall in wi’ the lads for they’re off and away

to take on the bold Hun with old Geordie McCrae.

REST IN PEACE, BOYS

The second supporting plaque commemorates McCrae’s sister battalion, the 15th Royal Scots. This was officially the 1st City of Edinburgh Battalion although it incorporated in its ranks more than 400 volunteers from Manchester, who had been disappointed by the War Office in their efforts to raise a Manchester Scottish battalion. The crests of Edinburgh and Manchester stand proudly side-by-side – as did the sons of the two great cities on the first day of the Somme. Again I chose a real soldier for the bronze relief. He’s John Brighton from the Blackley suburb of Manchester – posing in camp in 1915 and (opposite) in full trench ‘furry’ in 1916.

Finally we added a smaller (but no less important) bronze to the reverse of the cairn, expressing our gratitude in French to the local community for their support and their unstinting friendship. It was perhaps more fitting than we understood at the time, because over the last ten years we have indeed become fast friends.

From the outset our most vigorous supporter in France was the incumbent maire of Contalmaison, Bernard Sénéchal, who gifted us a small parcel of municipal land, adjacent to the church. Bernard insists that it used to be the village cricket pitch; I’m still not quite sure if he’s serious. Like the Scots, Bernard’s sense of humour is decidedly dry. There followed a short but successful campaign to obtain planning permission. The Contalmaison Cairn (as it was quickly becoming known) was portrayed as ‘the last of the Great War memorials’ – that is, not a new initiative, but the completion of a project first proposed to the War Office’s Battle Exploit Memorials Committee in 1919. Our friends in the Planning Department of the regional authority and in the Catholic diocese ensured that we obtained the necessary permissions in record time. All that remained now was finding the money.

***

The inaugural McCrae’s Battalion fundraiser took place in the Gorgie Suite at Tynecastle Stadium on 16 November 2003 in the notable company of Eddie Turnbull, the much-missed Bob Crampsey and Major-General Mark Strudwick of The Royal Scots. The generosity of those who attended was astonishing and within a few weeks we’d added important donations from the City of Edinburgh, the Scottish Executive, the Regiment, Heart of Midlothian Football Club and many others. Descendants of the battalion were matched in their kindness by countless supporters of Hearts along with followers of many other teams, including Hibernian, Raith Rovers and Falkirk. The McCrae’s ‘family’ had reassembled after more than eighty years. After a matter of months we’d raised enough money to get started.

It was important that the Cairn be unmistakably Scottish. After all, it commemorates a battalion from Scotland’s capital city. The plaques were cast in Nairn at Farquhar Ogilvie-Laing’s superb Black Isle Bronze Foundry. Work, meanwhile, moved quickly underway in France with the digging of a hole for the concrete foundations. The local contractor, who was specially vetted by Bernard for the task, discovered a great void directly under our site, caused by the collapse of rubble in what was probably an in-filled crater from a British howitzer shell. We needed a lot of concrete!

Watson Stonecraft sent out a skilled task force led by David Turner from Coatbridge. He was ably supported by father-and-son stonemasons, Atholl and Nicky McPhee. All the materials were carried to the Somme from Scotland: the Clashach sandstone from Moray Stonecutters in Elgin, and the Caithness slate paving from the Caithness Flagstone Company.

By then our logistic team had been augmented by my friend Julian Hutchings, Scotland’s unofficial ambassador to France. Julian is the founder and president of Alliance France-Ecosse. He appointed himself our ‘continental trouble-shooter’ and has since proved an invaluable asset at every stage of the project. We couldn’t have done it half as well without him. It’s a national shame that his selfless commitment to Scotland continues to go unrecognised in the country of his birth.

Work was completed only a week before the scheduled unveiling, when I was joined by Farquhar Ogilvie-Laing and Alvin Scott (whose grandfather, Jimmy Scott of Raith Rovers, was killed near Contalmaison on 1 July 1916) on a last-minute mission to mount the plaques. While the sun set over fields that once concealed a multitude of German machine-gun positions, we drilled our holes to the sound of distant gunfire as farmers hunted rabbits for the Sunday pot.

***

Bernard Sénéchal is exceptionally proud of his little village. He’s still quick to point out that the Cairn is not Contalmaison’s first battlefield monument. The local cemetery includes a memorial to nearly 600 men of the 12th Battalion of the Manchester Regiment who were killed or wounded during the assault on Contalmaison on 7 July 1916. It was placed there by their Old Comrades Association, who purchased the plot in 1929. And on 9 July 2000, just along the track that leads back to the village, the Green Howards and the Professional Footballers’ Association unveiled a memorial to the only English professional footballer to win the Victoria Cross during the Great War. 2nd Lieutenant Donald Simpson Bell of the 9th Yorkshire Regiment had played for Bradford Park Avenue in peacetime. After 34th Division was relieved at Scots Redoubt on the night of 3/4 July, Donald’s unit was among those who took over the position. He received his award for gallantry in attacking a German machine-gun in Horseshoe Trench on 5 July and was killed performing a similar deed near Contalmaison on 10 July, the day the village finally fell. Donald is buried nearby, at Gordon Dump Cemetery, where you’ll also find most of the lads from McCrae’s.

Our new memorial was in honoured company.

The Contalmaison Cairn was inaugurated on 7 November 2004 before a crowd of more than seven hundred visitors. Battalion families mingled with football supporters, curious locals and seasoned battlefield tourists. It was (and will remain) the largest gathering of descendants of a single battalion ever assembled. Sir George’s grandsons, George McCrae and Kenneth Hall, performed the unveiling. George had travelled all the way from British Columbia for the occasion.

The Service of Dedication was led by the Reverend Fiona Douglas, chaplain of Dundee University, whose grandfather, John Douglas, served as a sergeant in McCrae’s. Major-General Mark Strudwick, Colonel of the Royal Scots, delivered the main address and there were readings from Captain Gary Tait, M.B.E., Alan Owenson and Maire Bernard Sénéchal. Gary proudly carried the 16th’s Regimental Colour, which had been escorted out to France from its Edinburgh home.

Principal wreaths were laid by families of the battalion, followed by tributes from (among many others) the Great War Memorial Committee, Heart of Midlothian F.C., Hibernian F.C., and Edinburgh City Council. Rhona Brankine, M.S.P., attended on behalf of the Scottish Executive.

Sir George made his contribution, too. It was a grey, overcast morning. At the very moment of unveiling the clouds parted to reveal a rectangle of blue sky. Somewhere, up high, two crisp white vapour trails bisected each other to form a perfect saltire. Perhaps he knew that the time-capsule I’d placed inside the Cairn contained a small box of earth from his Edinburgh grave.

It was a profoundly moving occasion, characterised by a wonderful sense of comradeship – epitomised by the two official representatives of Hibernian Football Club, Tom Wright and Stephen Dunn, cheerfully pushing Jeanie Heron, the 90-year-old niece of a dead Hearts player two miles uphill in a borrowed wheelchair. We would not see its like again.

Or so we thought!