Contalmaison Village

BEFORE THE WAR Contalmaison was the seventh largest village on the Somme – with 72 houses and more than 300 inhabitants, who made a sparse living cultivating the neighbouring champs and grazing a few small herds of cattle. There was a church, a school, a café, a tennis court in the village square, and a grand country villa, known as Contalmaison Château.

The village stands on a spur of the Pozières Ridge and commands fine views of the surrounding countryside. Strip away the trees, and the fields of fire are excellent in all directions. The Germans arrived in 1914 and immediately protected every approach with dense aprons of barbed wire. They were cunning enough to leave visible ‘weak’ spots – to lure advancing troops into gaps covered by hidden machine-guns. The locals still talk about the awesome killing power of the mitrailleuse. One well-placed man with a steady disposition could wipe out an entire battalion.

There were many such killing zones in the German position. The Pozières Ridge was dotted with fortified villages, linked together by a network of wired entrenchments, fiendishly designed to take advantage of every fold in the ground. Contalmaison was an important strongpoint in the German support line, a supply base for the adjacent front line village of La Boisselle, which guarded the old Roman road from Amiens to Bapaume. La Boisselle (in the opinion of both British and German generals) held the key to success or failure of the forthcoming operations on the Somme.

On 29 June 1916 with the German position undergoing its sixth night of uninterrupted bombardment, the headquarters of 110 Reserve Infantry Regiment moved back from La Boisselle to the relative safety of Contalmaison. The cellars of the partially ruined château had already been requisitioned as a field hospital and casualties from high explosive and shrapnel were crammed into every available corner. The long communication trench to La Boisselle was now blocked and the telephone connection to nearby Pozières had been severed. Contalmaison was cut off.

At 10.17 on the evening of 30 June the subterranean listening post at the tip of La Boisselle (known as Moritz 28 North) intercepted a telegraph message from British Fourth Army HQ, wishing good luck to the battalions taking part in the morning’s assault. The information was relayed to Contalmaison by phone and from there to Pozières by runner. Within an hour the entire German position on the Somme had been alerted to the impending offensive.

At 7.30 a.m. the barrage lifted from the front line and the machine-guns caught the rows of khaki soldiers stumbling forward into the uncut wire. Contalmaison was initially untroubled. Isolated groups infiltrated the German trenches with bomb and bayonet but were unable to hold on to any gains. The Tyneside Scottish battalions of 102 Brigade already lay dead or wounded in the fields in front of La Boisselle; the left flank battalions of 101 Brigade had almost ceased to exist. It was left to the Royal Scots battalions to carry the advance, supported by small parties of Tyneside Irish who had survived the slaughter on Tara Hill. They reached Wood Alley and bombed their way into Scots Redoubt. On the right Birch Tree Trench offered some shelter but also took them across the divisional boundary into XV Corps territory. Beyond Birch Tree Trench was a small stand of trees known as Peake Wood; beyond the wood the ground rose steeply towards yet another heavily wired entrenchment, an extension of the Kaisergraben ‘intermediate’ system. British Artillery observers had named it ‘Quadrangle’.

Quadrangle Trench curled around the southern approaches to Contalmaison like a protective hand, cutting through the cellars of a single outlying house on the Fricourt road. On either side of that road were two machine-gun strongpoints, Leith Fort and Edinburgh Castle. The village itself was not strongly garrisoned, but the sudden and unexpected British penetration to Peake Woods roused the commanding officer to improvise a response. Regimental clerks, transport men, labourers and medical orderlies were assembled in the square and moved down to Quadrangle at roughly the same moment that young George Russell crossed the trench and began to climb into the village. He disappears from the page at that point.

Michael Kelly, Russell’s corporal, organised a hasty withdrawal as ever more Germans appeared. With most of his command wounded Kelly single-handedly dispatched a group of enemy signallers with his bayonet and captured one of their flags. Survivors of the 16th Royal Scots insisted he deserved to be awarded the Victoria Cross for his conduct that morning. In the absence of commissioned witnesses, the recommendation was refused. Kelly himself was (according to his daughter) unmoved. ‘Do you think that a wee bit of bronze could make up for losing my pals? Dinna worry yourself, lassie, for it’s no loss to me.’

George disappeared – along with most of the 16th Royal Scots who died that morning. They are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing and have no known grave – although there’s an excellent chance that you’ll find most of them among the 1,053 unidentified burials at Gordon Dump Cemetery, near la Boisselle. Nineteen McCrae’s lads have named headstones there – including Murdo McLeod (‘Scotland’s Strongest Man’) and Lionel Coles, commanding officer of the footballers’ company.

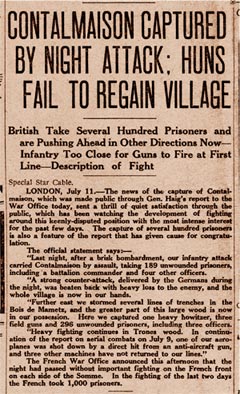

Contalmaison finally fell on 10 July, the day that Donald Bell was killed. It was briefly recaptured during the German offensive of 1918 but the Armistice brought peace, reconstruction and a return to bucolic anonymity. Eight young men from the village had given their lives in the war – including three members of the Marienne family. A marble tablet listing their names was placed in the rebuilt church. Late in 2010 McCrae’s Battalion Trust was honoured to be asked by the conseil municipal for permission to erect a new ‘outdoor’ village memorial beside the Cairn. It was a humbling request (to which we readily acceded) and on 3 September 2011 the Contalmaison Village Memorial Stone was unveiled. Cairn and Stone stand side-by-side – as did the soldiers of Scotland and France in what their respective governments were pleased to call The Great War for Civilisation.

As for Contalmaison Château, it was never rebuilt. In its place you’ll find a Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery which dates from the middle of July 1916, when the cellars were being used by British and Commonwealth field hospital units. Eighteen German bodies were removed from the grounds after the war and reburied in the large German cemetery at Fricourt. John Smith, a private in B Company 16th Royal Scots, was wounded in the shoulder on 1 July and picked up by a German soldier who helped him back to the château for treatment. He thought he was going to be shot. He spent the next nine days huddled in the cellar under constant British bombardment. On 10 July, a bomber from the Green Howards, who was busy liberating the village, heard movement inside and tossed down a couple of precautionary Mills grenades. They detonated immediately in front of Smith, fracturing his leg. ‘I should have been killed,’ he wrote in a letter to his parents. ‘You can guess I have been shaking hands with myself ever since.’

I’ve been shaking hands with myself, too. I consider myself privileged to have been involved in the Cairn project, treading in the footsteps of a group of men I greatly admire. Their ‘unfinished business’ is finally complete – although it leaves us mere mortals with fresh challenges for the future. A landmark on the Western Front is what D.M. Sutherland envisaged in 1919. I think he’d be proud of what we’ve managed to deliver.

Jack Alexander

Edinburgh

February 2014